Neuroscience or neurobabble?

There is a continuing and increasing trend to attach the term ‘neuro’ to articles, products and services in psychology and people management. It is claimed that organizational behaviour, leadership and learning and development, can be better understood and improved using neuroscientific theory and methods.

Looking at leadership competency development in particular the question is how much of this is based on science and how much is just ‘neurobabble’ ?

What is neuroscience ?

Neuroscience is the study of the function and structure of the nervous system. There are many sub disciplines. Those that are relevant to organizations include the following;

- Behavioral neuroscience – how the brain affects behavior

- Cognitive neuroscience – how the brain affects thinking

- Cultural neuroscience – the interaction between beliefs, practices and values and the brain, mind and genes.

The investigation of what is happening in the brain is done by various forms of imaging.

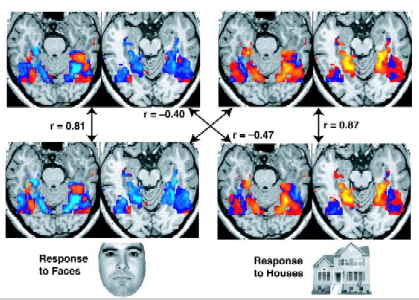

- fMRI – (functional magnetic resonance imaging) creates pictures of blood flow in the brain to detect areas of activity.

- EEG – (electroencephalogram) maps electrical activity in the brain using electrodes placed around the head.

- PET (positron emission tomography) uses a radio active tracer after these have been absorbed into the glucose in the bloodstream. Areas of activity have greater utilsation of glucose than others.

White and grey brain matter does not contain blood so fMRI and PET are looking at the blood supply near these areas. EEG is measuring brain activity more directly. However while EEG has a more accurate result in terms of time – and therefore relationship of stimulus and response, fMRI and PET are more accurate in terms of location of activity.

Most brain imaging has been done whilst people are looking at images or video. EEG studes can be done while people are engaged in activities.

Neurofeedback

Neurofeedback is a self-regulation technique providing individuals with feedback about specific levels of (electrical) brain activity in conjunction with specific target behaviors. Neuroscientists generally assume that this type of feedback can help individuals “entrain, change, and regulate neural activity”1

Proponents typically play a pleasant sound when ‘positive’ brain patterns are seen and an unpleasant one where undesirable brain patterns are seen. This is a form of operant conditioning – albeit unconscious. It is claimed repetition will build positive brain patterns associated with target behaviours.

Why is it relevant?

Studies show that the brain has neuroplasticity. By this we mean that the connections between brain cells can change in terns of their responses to other neurons in the network and in the formation and strength of these connections. This circuitry responds to changes in the indvidual’s environment. This is the process that underlies learning. The differences in these brain circuits are what make the differences between people and their perceptions of the world.

Neurogenesis means the growth and development of neurons. Most of this occurs in the womb. In adults neurogenesis is thought to be very slow and to occur only in some areas of the brain such as those involved in memory. It may be positively influenced by sleep, physical exercise and the extent of learning.

Obviously learning is a central issue and interest in organizations today whether it be for job specific skills or soft skills such as leadership and collaboration.

What are the problems? Why the term neurobabble?

It is important to understand that changes at the neuron level of the brain are not the same thing as changes in observable behaviour. While there may be some correlations at a very high level our ability to examine what is occurring in the brain is limited to observations of electrical activity on the skull and scalp, blood flows around the brain and their glucose content.

Various critical terms have been coined to describe the over – generalization of findings from neuroscientific studies to applied settings such as workplaces;

- Neuromyths

- Neuro-Nonsense

- Neurobabble

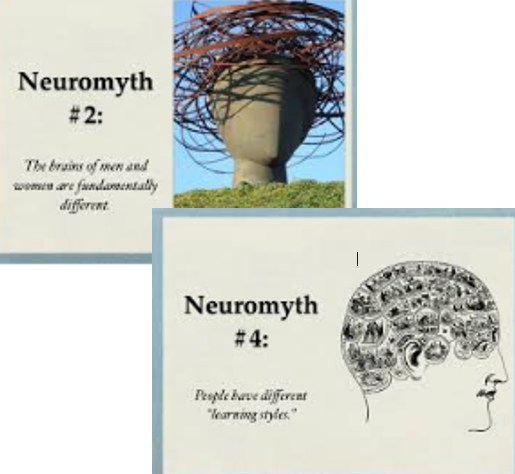

Neuromyths are misconceptions about the brain that propagate when cultural or social conditions (e.g. lack of critical thinking or expert knowledge, unconscious biases, etc.) inhibit rigorous scrutiny 2

Such misconceptions about neuroscience are promoted by the popular press and by vendors who know that neuroscientific language sells their products and services.

Because neuroscience delivers images of the brain most of these beliefs are about the location of activity in the brain. For example the belief of many educationalists that learning and development is optimised when students are taught in their preferred learning style. This is based on the assumption that some parts of the brain associated with visual, auditory or kinaesthetic information processing may function better than others in an individual. In fact, while people certainly have preferences for different media, the effectiveness of this method has not been borne out by controlled lab studies, or in other academic research.

While there are undoubtedly specialised areas in the brain for particular activities these areas don’t operate in isolation but as part of a complex network. While we can observe at a very crude level the brain patterns associated with particular activities, every individual is unique in the detailed way their neural ntwork is connected and functions.

The problem with neuroscience studies themselves is that most have very small numbers of subjects. This is because most are based on brain imaging which is expensive, and requires special facilities. Small samples can only give low statistical power and effect size. This means a high risk that the observed effects are over-estimated. Further such small studies are hard to reproduce, and there is a strong possibility the original result will not be substantiated.

Finally many neuroscience studies are done with animals – laboratory rats. Results of these may not be applicable to humans.

Can we learn anything useful from neuroscience for Leadership Development?

There are a number of findings from neuroscience that underpin previous findings in psychology in respect of learning3;

- Use it or lose it – failure to activate particular brain functions may cause that circuitry to be lost.

- Use it to improve it – use of specific brain areas can enhance its circuitry.

- Repetition works – for lasting circuitry change repetition is required.

- Intensity is needed – difficulty and challenge promote stronger neural patterns

- Younger brains learn better

- Relevance matters – emotion, attention and motivation are associated with better learning (circuitry)

It is claimed that insights from neuroscience can lead to better theories of organizational behaviour including leadership.

Some recent studies are said to illustrate the potential benefits.

1. Setting and achieving goals – behaviour change 4

A goal is something we want to achieve that is unlikely to happen by itself – without some effort from us. It involves behavior change – doing something differently. Two things are needed – cognitive ability; relevant knowledge and skills, and motivation.

Executive function in the frontal areas of the brain are involved in behaviour change because this involves the effortful, conscious allocation of mental resources to novel tasks. The executive function has limited capacity (bandwidth) at any one time. This effort has an opportunity cost. So motivation and priority are important. An environment that is distraction free (of alternative opportunities) is helpful.

From a neural perspective it is important to make the goal behaviour a habit as quickly as possible so that the executive function is no longer needed. Successful habit learning requires the activity be preceded by consistent cues and then rewarded, as well as sufficient repetition to establish automatic behaviour.

2. Coaching 5

A recent study reports on fMRI imaging of two small samples of graduate students following coaching by post doctoral students. Two different coaching approaches and coaches were used. One asked the sample to articulate their personal vision, or what their ideal life and work would be 10 to 15 years from now. The other asked participants to focus on the challenges they were experiencing in meeting the expectations currently placed upon them. A subsequent questionnaire found that the coach using the envisioning method was perceived significantly more positively than the other. A few days later the imaging study presented a simulation of coaching with videos of the 2 coaches talking, they made a response by making a key press and then saw a video of the coach thanking them. The coach who was perceived more negatively was associated with activity in brain areas associated with stress and self-consciousness in line with the questionnaire results. The coach who asked participants to envision the future was associated with activity in areas of the brain asociated with visualisation, positive emotions and social connection.

The inference made is that in the coaching process it is best to start from the positive vision of one’s self and one’s strengths and review feedback in that context.

3. Leadership practices for building trust

It has been suggested that the release of the hormone oxytocin, produced in the brain, is involved in trust and prosocial behaviour. However some studies also highlight that oxytocin production is also associated with stress and separation anxiety.

A recent study finds that oxytocin’s effect on collaboration within a team is mediated by cognitive style. Oxytocin by nasal administration increased collaboration for intuitive thinkers but reduced it for reflective thinkers.

Even though the effect of oxytocin may not be straightforward it is proposed that a number of management practices can be used to build trust through the generation of oxytocin.6

- Recognition (especially public)

- Common goals

- Autonomy to decide how and when to work together

- Self determination – allowing staff to decide when to take holidays

- Openness and information sharing

- Caring culture

- Investing in people’s personal growth

- Leaders with integrity

Unfortunately despite the claims it is a gigantic leap to infer the effectiveness of these practices from a few laboratory studies correlating empathy with oxytocin release.

4. Building Resilience7

Successful leaders need to be resilient. Resilence from the effects of adverse events, stress and anxiety.

There are two major activity networks in the brain. One responsible for refleXive activity – rapid automatic processing including perceptions, emotions and cravings. This is based mainly in the lower areas of the brain. The other is responsible for more controlled processing – refleCtive activity, and is based in the cortical regions. These systems are often known as the X and C systems.

While the C system can to an extent control the X system – moderating emotions, fear and impulses, the X system can also affect the C system when overwhelming negative emotions, fear and stress disrupt its limited processing capacity.

Fear is learnt through classical conditioning – the repeated direct association of an event with an adverse consequence. Also by observation and by information. Fear responses are extinguished when the event occurs without the adverse consequence – in a safe environment.

Potential threats or stressors trigger automatic flight, freeze or fight responses which increase heart rate, inhibit digestion and release the stress hormone cortisol which stimulates the release of glucose into the blood stream. In modern life these reactions are triggered by anxiety causing heart disease, ulcers, and changes in the brain that can lead to continuing anxiety, memory and attention issues.

As we have known for some time there are techniques for dealing with stress and anxiety. Primarily;

- Regulation of emotion by talking about it, expressive writing

- Cognitive therapy – to identify the thoughts that trigger emotions and reframe them in a more rational or positive way

- Mindfulness

- Stress innoculation – exposure to manageable fearful stimuli in safe situations – facing the fear

- Active, deliberate avoidance of stressful situations and

- Adoption of a ‘fighting spirit’ because coping is better when there is perception of control

- Social Support systems

- Healthy living – adequate sleep, avoiding excess alcohol and drugs, healthy eating, dietary restriction, physical exercise.

- Expressing gratitude to oneself and others

5. Using Neurofeedback for Leadership Development

Waldman and colleagues used EEG to ascertain the pattern of brain activity exhibited by leaders while undertaking a task on company vision, considered a key part of the inspirational leadership style. They found apparently distinct brain patterns in the frontal brain regions that distinguished inspirational from non-inspirational leaders, and advocated for the use of neuro feedback to develop leadership competencies.

Neurofeedback is now a thriving industry. However studies do not follow the classic double blind format expected of clinical research. In fact it seems there is a strong placebo effect where participant motivation, interaction with the instructor and belief in the technology all have strong effects. Just understanding and believing that the brain can change can provide the expectation of success that is a powerful mechanism for change seen in the placebo effect. There is currently no evidence that a neurofeedback intervention itself is of any benefit.

What is certain is that the tools of neuroscience are not able to measure the subtle, complex and situation dependent thinking which is the hallmark of effective leadership.

There is a danger that …

“organizational justice is compromised by a reification and fetishization of brain signals assumed to be as—if not more—relevant than the actions of an employee and the opinions of her colleagues.” 8

Summary

It is evident that the neuroscience data is simply reinforcing what we already know from decades of research in psychology, rather than suggesting new approaches to leadership development.

It is not clear yet that observing the brain has anything significant to add to the many well controlled and validated studies in organizational psychology.

Be wary of any claim, product or service that includes the term ‘neuro’ .

The Centranum Competency Platform provides a easy and effective way to define leadership competencies, assess leaders, including with 360 feedback. track capability gaps and development progress. Learn More

References

1. Thibault, R. T., Lifshitz, M., & Raz, A. 2016. The self regulating brain and neurofeedback: Experimental

science and clinical promise. Cortex, 74: 247– 261.

2. Grant A.M. (2015) Coaching the brain: Neuro-science or neuro-nonsense? The Coaching Psychologist, Vol. 11, No. 1, Jun

3. Nowack, K, Radeci, D. (2018) INTRODUCTION TO THE SPECIAL ISSUE: NEURO-MYTHCONCEPTIONS IN CONSULTING PSYCHOLOGY—BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research Vol. 70, No. 1, 1–10

4. Berkman, E. (2018). The neuroscience of goals and behavior change: Lessons learned for consulting psychology. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 70, 28–44.

5. Boyatzis, R., & Jack, A. I. (2018). The neuroscience of coaching. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 70, 11–27.

6. Zak, P. (2018). The neuroscience of high-trust organizations. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and

Research, 70, 45–58.

7. Tabibnia, G., & Radecki, D. (2018). Resilience training that can change the brain. Consulting Psychology

Journal: Practice and Research, 70, 59–88.

8. Lindebaum, D., Almoudi, I., Brown, V.L. (2018) DOES LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT NEED TO CARE

ABOUT NEURO-ETHICS? Academy of Management Learning & Education Vol. 17, No. 1, 96–109.