What is Organizational Efficiency?

The establishment of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) — officially transitioned from the U.S. Digital Service on January 20, 2025 — has placed workforce efficiency under a national microscope. Under Elon Musk’s guidance as senior advisor, DOGE embeds tech-driven reforms across U.S. federal agencies with a clear mandate to streamline operations and reduce costs. This renewed focus offers a timely context for examining organizational efficiency and the factors that contribute to — or detract from — it.

In this report, we define efficiency and examine the research linking competence and competency management systems to improved organizational performance.

What is efficiency? Efficiency versus Effectiveness

Efficiency is doing more with less — maximizing output while minimizing input. Organizational efficiency refers to how well an organization uses time, money, people, and technology to deliver results with minimal waste. It’s not the same as organizational effectiveness – whether the right goals are being met. An organization may be efficient in execution but ineffective if producing a product with no market demand.

Global trends in efficiency/productivity

A continuing efficiency problem

Even before the onset of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 the rate of productivity improvement had slowed in most developed economies. This reflects the increasing importance of service industries where productivity gains from automation are harder to achieve.

Then the COVID epidemic caused a collapse in productivity from which many economies have not yet fully recovered. The financial stimulus applied to counter the epidemic has resulted in growth of government workforces and programmes that are prone to inefficiencies and waste.

How is efficiency measured?

In a number of ways – output per worker, return on investment, speed of delivery, error rates, or energy use, for example.

Across industries, efficiency is heavily influenced by rapid advancements in technology, shifting workforce dynamics, and economic pressures. Most organizations are adopting digital tools like artificial intelligence (AI), automation, and data analytics to streamline processes, cut costs and streamline decision making and collaboration across teams.

Industry Differences

Advancing

Some industries have been quicker or more easily able to leverage technology to gain efficiency.

Technology (especially Software Services)

Has low physical overhead—no factories, minimal raw materials—and scales easily through digital distribution. Automation, AI, and cloud computing let companies churn out high-value products with lean teams. Labor productivity is sky-high; a small group of engineers can serve millions of users.

Financial Services ( larger players)

Digital banking, algorithmic trading, and fintech platforms process huge numbers of transactions using AI-driven fraud detection and automated workflows with minimal human intervention. Their revenue per employee is staggering – as much as $500,000.

Lagging

In contrast some industries and organizations struggle with structural inefficiencies, often due to complexity, regulation, and/or resistance to change.

Healthcare

Despite tech investment, though often limited by finances, healthcare wastes resources through fragmented and incompatible systems, redundant administrative tasks, (in the USA administrative costs can account for 25-30% of total spending) and slow adoption of new management systems. A huge emphasis on safety and the need for regulatory compliance adds layers of cost.

Construction

Productivity has been flat for decades. The reason – heavy reliance on manual processes, dependency on weather and skilled labour shortages as well as site-specific engineering and safety challenges. In addition poor coordination between contractors compound delays and increase costs leading to frequent project time and cost over -runs. Safety and other regulatory compliance requirements also add to costs. A move to pre-fabrication and modular construction has improved efficiency for some types of construction.

Local and Central Government

OECD data shows public institutions generally lad behind the private sector in productivity.

Bureaucracy, lack of competition, and misaligned incentives (e.g., ineffective performance management) lead to bloated processes and slow decision-making. System upgrades face challenges of entrenched legacy systems and lack of political agreement as administrations change.

Strategies to improve efficiency

There are three basic ways to enhance efficiency:

- Increase output or sales volume

- Raise prices while maintaining volume

- Reduce costs — particularly labor inefficiencies

While non-labor inputs can be cut with cost reviews, labor requires more careful analysis:

- Identify and reduce non-value-adding activities (e.g., rework, downtime)

- Improve task execution by raising competence

Workforce Competence

What is Competence?

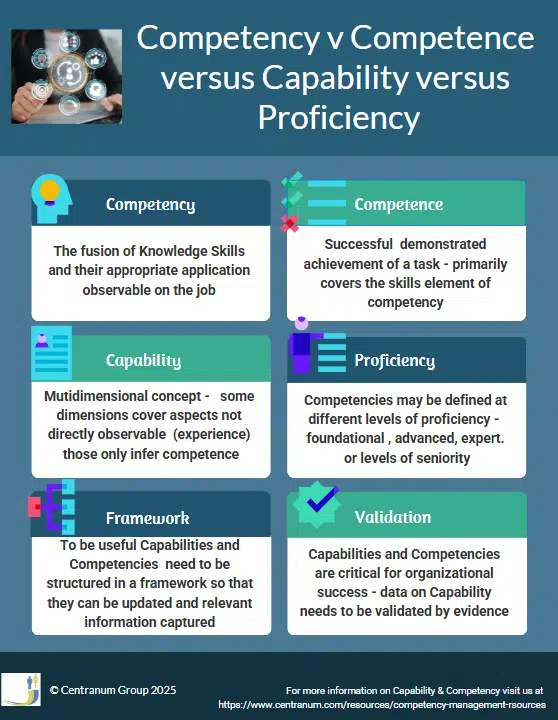

Competence is often confused with competency. Competency is a composite concept covering knowledge, skill and their appropriate application in context – i.e. on the job. It is an action concept. In contrast competence is a state – a snapshot in time. It may be a competent or not competent dichotomy. Alternatively it can be described by degrees – a level of proficiency.

Competence is often assumed from qualifications, training and job experience – but these only imply competence. In fact research over many decades has consistently shown that only 10-30% of training content actually transfers into sustained on job performance.

Competence and Employee Performance - how are they linked?

There are several mechanisms by which individual competence contributes to organizational efficiency.

Task performance – Competence drives performance: Technically competent employees perform their tasks more effectively, reducing errors, improving quality, and enhancing overall productivity. Competent individuals possess the technical skills and knowledge required to execute their roles proficiently. minimizes errors and rework, which are significant drains on organizational resources.

Collaboration and Team Dynamics. Interpersonal skills, such as communication, emotional intelligence, and teamwork facilitate effective collaboration , knowledge sharing, and conflicts resolution. Efficient teams reduce delays caused by miscommunication or misalignment, thereby boosting overall organizational productivity.

Reduced Training and Leadership costs Highly competent employees require less oversight and ongoing training, freeing up managerial resources and reducing costs.

Competence fosters innovation: Skilled employees are more likely to engage in creative problem-solving and critical thinking, enabling individuals to identify inefficiencies and propose improvements.

Agility and Organizational Learning Competent employees demonstrate adaptability learning new tools, processes, or strategies as needed. This flexibility allows organizations to pivot quickly in response to market shifts or technological advancements without incurring significant retraining costs or operational disruptions.

Competence aligned with strategy: When employees’ competencies are aligned with the organization’s strategic goals, through the use of competency frameworks and competency based HR processes, the efficiency of operations improves.

Practical Implication

Organizations looking to improve task performance and reduce waste should start by identifying key technical and interpersonal competencies for each role. Using these as the basis for development planning and performance evaluation helps align day-to-day execution with strategic goals.

Workforce Competency & Efficiency - the evidence

Task performance

Robust evidence from I/O psychology1demonstrates that job knowledge—commonly equated with technical competence—is one of the most predictive factors of individual task performance. Foundational studies Meta-analyses (Hunter 1986, Schmidt & Hunter 1996) show correlations between job knowledge and performance ranging from r = 0.48 to 0.63, validating the core premise of competency management initiatives. Other studies (Salas et Al 2001, Blume et al 2010) find that task-specific training that reflects the actual work context delivers the greatest gains in job performance and efficiency.”

Hackman & Wageman (2005) found that team coaching that enhances task competence (e.g., skill-building) improved performance on complex tasks. Across 20+ studies reviewed, coached teams showed measurable gains. Those with structured coaching achieved an average of 22% increase in efficiency

Weaver et al. (2014)In a study of 30 hospitals found that Nurses and doctors trained in task-specific protocols via simulations reduced procedural errors by as much as in 19%.

Practical Implication

Use contextualized training and coaching to build task-specific competence for real-world impact.

Core Competencies

A 2020 study in the financial sector has confirmed previous research findings that some core competencies – especially communication, social competence and teamwork contribute to organizational performance.

Core competencies are also important but their effect on efficiency is indirect and hard to quantify.

For core competencies, Marek Jabłoński in his book chapter “Employees’ Skill Requirements Caused by Technological Progress” has identified the core skills of critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving as essentials in the current operating environment. Most advisors now include Digital Competence as a core skill – the use of ICT tools for communication and management.

Looking forward, the 2025 World Economic Forum Future of Jobs report highlights the increasing demand for the following skills.

- Creative thinking

- Resilience, flexibility and agility

- Curiosity and lifelong learning

- Leadership and social influence

- Talent management

Impact of HR Practices

Huselid (1995) in a seminal study on high performance HRM practices (e.g., training, selective hiring) improved employee productivity across 968 U.S. firms by enhancing competence and reducing turnover. The study found that a one standard-deviation increase in HRM practices above the average was associated with $27,044 higher sales per employee annually (1991 USD), reflecting productivity gains.

Teamwork and Collaboration

As you might expect, there are many studies showing the impact of improved teamwork and collaboration on organizational efficiency.

From a psychology perspective DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus (2010) found that teams with a high shared cognition (e.g., mutual understanding of tasks) performed better across 65 studies. There was a moderate correlation r = 0.34 of performance improvement with strong team coordination and communication.

Shaw et al. (2008) found that in steel mini-mills, teamwork increased productivity by up to 15% in complex lines – those with many interdependent tasks.

Boyatzis et al. (2012) in a study using 360 degree feedback on emotional and social competence found those leaders with high competence were associated with qualitative improvements in team climate and performance.

In a study of 75 Manufacturing plants, Dunlap et al. (2016) found that assembly line teams assessed as more collaborative had better efficiency, up to a 21% reduction in cycle time (d = 0.54) with strong team coordination.

Likewise two studies of healthcare teams found relationships between teamwork competence and performance.

Hughes et al (2016) in a meta analysis of 129 studies of clinical team training found at 15% reduction in patient mortality (d = 0.39), directly linked to improved teamwork competence.

Schmutz et al. (2019) – in a meta analysis of 31 studies with 1,390 healthcare teams found that effective teamwork processes (e.g., coordination, communication) moderately improved team performance.

Practical Implication

Investing in teamwork training, shared task models, and team-based feedback (e.g., 360 reviews) pays off in operational environments. Use structured assessments of collaboration and communication skills, especially in roles with high interdependency.

Innovation

Innovation – especially technical innovation should promote efficiency. Innovation and creativity need information sharing and discussion as well as an open environment that encourages new ideas and experimentation.

In a study by Anderson et al. (2014) the meta analysis of 96 studies on team innovation found that teams with collaborative cultures were more innovative – a moderate effect, obviously there are many other variables that impact innovation.

Battistelli and colleagues (2019) investigated information-sharing and learning competence in 756 military employees and found that these competencies positively affected innovative behaviour mediated by self efficacy. Again only a moderate effect.

Finally Mckinsey in their Future of Work after Covid-19 report (2021) found that Tech firms with digitally skilled staff were more adaptable and saw faster innovation (e.g., new features). They found a general 20-25% productivity gain across digitised sectors though not directly attributable to innovation.

Practical Implication

Foster open environments and collaborative skills to drive innovation. Track knowledge sharing and learning agility.

Innovation requires both technical competence and collaborative mindset. Organizations should track these skills as well as frequency of idea generation.

AI competence

The following studies demonstrate that AI competence significantly boosts task efficiency, particularly in professional, technical, and knowledge work domains. Two of the studies do not investigate quality of output. The one that does indicates the increase in productivity was less when quality of output was considered.

Generative AI can be unreliable and so for those tasks requiring accuracy additional checking is needed and there may not be significant productivity benefits.

A study of 500 developers by Tambe et al (2019) found a 35% reduction in time taken to complete tasks for those skilled in using AI assisted development tools.

A later study by Li et al (2021) found a similar result in their study if 1200 developers – a 41% reduction in task time.

In the personal arena Noy and Zhang (2023) experimenting with over 400 professionals using AI tools such as ChatGPT found they completed tasks such as writing and analysis completed tasks 55.6% faster than the control group but when adjusted for quality the increase in productivity was less – 25%

Practical Implication

To benefit from AI, employees need foundational digital competence and support in tool-specific training. Develop digital competencies for AI tool usage, especially in writing, analysis, and code generation. Quality assurance still required.

Generative AI tools are most useful in creative or drafting tasks — but require review for quality-sensitive work. Organizations should define “AI-augmented” competencies within role profiles and train accordingly.

Leadership competence

Leadership competencies have a profound effect on organizational success and reports consistently show that there is a need to improve them.

In a small but widely quoted study of the effect of emotional intelligence on job performance Côté et al (2006) examined 170 university employees on ability based emotional intelligence, (self-awareness, empathy, and emotional regulation), general intelligence, task performance and organizational citizenship behaviours.

They found that both emotional and general intelligence predicted improved task performance and organizational citizenship behaviours. The effect was greater in those with lower general intelligence.

A meta analysis of 112 studies with over 39000 participants focusing on core leadership competencies like trust-building, shared decision-making, motivational communication, confidence-building found that these competencies significantly enhance operational efficiency through improved team functioning and engagement. Dunst et al (2018).

Bonini et al (2023) in a systematic review and meta analysis of transformational leadership competencies (vision setting, delegation, support) found that, especially in rapidly changing environments, these skills helped organizations respond more efficiently to change. A moderate effect.

Finally, as might be expected digital leadership competencies – vision for technology adoption, digital communication, agility) when combined with leadership competencies of strategic thinking and influence. In a study of 500+ senior managers across manufacturing, logistics and finance organizations – Merrill et al (2022) found that in organizations with strong digital leadership innovation cycle times were 20% faster and operational process efficiency was 18% higher.

Practical Implication

Invest in leadership development focused on strategic thinking, communication, and tech adoption.

The Impact of Competency Management Systems on Organizational Efficiency

There is a lack of quantitative research on the impact of competency based management systems on organizational efficiency.

An article in Nature refers to studies that indicate it is not particular competencies, but the mix of competencies particular to the organizations context, that makes the difference

The research into competency mismatch provides an indication of the significant impact of competency on productivity.

Mismatches may be based on education or on skills. Those who are over skilled, usually older workers, can perform lower level jobs but are more costly, adversely impacting productivity. Those with lower skill levels are less costly (but also less likely to be employed).

The IZA Institute of labour study found efficiency costs to vary between 1-9% with an average of 3% for skills mismatch. The key factor was not the proportion of mismatched workers but their costs relative to the well matched worker. One study of the effect on individual productivity using the O*Net multidimensional skills model found mismatch could affect output by 7%. The gap is highest for cognitive skill mismatch.

Data on EU Skills Mismatches and Productivity indicates that

” when comparing a mismatched with a well-matched worker within the same occupation, overqualification raises and underqualification reduces productivity. When comparing a mismatched with a well-matched worker within the same qualification level, overqualification reduces and underqualification increases productivity.”

A study by the Swedish Ratio group found that on a purely labour cost versus output basis, in manufacturing firms, over educated workers are more costly and therefore negatively impact productivity – whereas under educated workers have a lower cost and potentially positive impact on productivity.

A more recent study used AI to classify worker to job match based primarily on education and experience. They found a strong link with productivity and also of better employee job allocations with higher managerial competence.

Comprehensive CMS practices—including defined competencies, robust assessments, and targeted development—can reduce mismatch and improve efficiency.

A study of Indonesian manufacturers and supply chain and quality activities (Tarigan et al. (2021) measured Competency Management activities – competency definition (e.g., IT/interpersonal skills), assessment, and targeted development. They found that the use of competency management processes was linked to better supply chain integration, quality, operational capability and performance.

Djalab et al. (2023) assessed the impact of competency based management in two Algerian colleges – recruitment, assessment, development, compensation. They found that it significantly increased organizational learning, a key focus for the organization.

Ensuring employees are properly matched to roles based on competency assessment significantly enhances firm-level performance.

Skills gaps and poor alignment directly reduce productivity—potentially up to nearly a one-fifth drop in value added per employee.

Comprehensive CMS practices—including defined competencies, robust assessments, and targeted development—can reduce mismatch and improve efficiency.

Practical Implication

Implement CMS practices — define competencies, assess regularly, and link results to learning plans.

Systems that define and track role-based competencies reduce skills mismatch, optimize staffing, and support strategic workforce planning. Prioritize clarity in competency definitions, consistent assessment, and a feedback loop that connects performance data to development plans.

Competency as a Driver of Organizational Efficiency

Decades of research, reinforced by more recent firm-level and meta-analytic studies, confirm that workforce competence is a foundational determinant of organizational efficiency. Competencies—defined and managed through structured systems—impact performance in multiple dimensions:

Task Performance: Studies consistently show that employees with clearly defined and role-relevant competencies complete tasks more accurately, quickly, and with fewer errors—directly enhancing productivity and reducing operational waste.

Team Collaboration: Core competencies such as communication, coordination, and shared mental models improve team-based output, particularly in high-stakes environments like healthcare, manufacturing, and project-based work.

Innovation: Organizations that foster learning competencies and collaborative climates report significantly higher innovation rates and faster product development.

Leadership Impact: Leaders with strong interpersonal and strategic competencies create alignment, boost team engagement, and drive more consistent execution—contributing to system-wide efficiency.

Digital Enablement: Digitized competency evaluation and management systems further enhance efficiency by enabling consistent assessments, automating gap analysis, and aligning learning with performance needs.

Mismatch Costs: The absence of competency alignment—manifesting as over- or under-skilled employees—leads to measurable productivity losses at the firm level, ranging from 1–20% or more depending on the severity of mismatch.

Ultimately, a well-implemented competency management system (CMS) acts as a multiplier for human capital—enabling the right people, in the right roles, with the right skills, at the right time. When competencies are actively defined, assessed, and developed, organizations gain not only efficiency but also agility, resilience, and long-term performance advantages.

Implementing these research-backed practices doesn’t have to be complex. Centranum’s platform helps you define, assess, and develop competencies at scale — across roles, teams, and locations. Learn more about the platform

From Insight to Action: Building Efficiency Through Competency

The research is clear — competence is not just a contributor, but a critical enabler of organizational efficiency. The challenge is operationalizing it. That means defining what competence looks like in your context, assessing it reliably, and using the data to guide role clarity, development, and talent deployment.

Whether through AI-assisted frameworks, competency libraries, or more structured CMS platforms, the organizations seeing efficiency gains are the ones turning these insights into systems — making competence visible, measurable, and aligned with strategic intent.

References

¹ https://smallbusiness.chron.com/organizationalefficiency-factor-37839.html

Hackman, J.R., & Wageman, R. (2005). A theory of team coaching. Academy of Management Review, 30(2), 269–287.

Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38(3), 635–672. https://doi.org/10.2307/256741

Shaw, J.D., Gupta, N., & Delery, J.E. (2008). Stanford case studies and field research.

Weaver, S.J. et al. (2014). Team-training in healthcare: a narrative synthesis of the literature. Academic Medicine, 89(9), 1251–1261.

Schmutz, J., Meier, L.L., & Manser, T. (2019). How effective is teamwork really? The relationship between teamwork and performance in healthcare teams: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open, 9(9), e028280.

Hunter, J. E. (1986). Cognitive ability, job knowledge, and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(1), 72–81.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (1998) The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 262–274.

Salas, E., & Cannon-Bowers, J. A. (2001). The science of training: A decade of progress. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 471–499.

Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., Baldwin, T. T., & Huang, J. L. (2010). Transfer of training: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Management, 36(4), 1065–1105.

Boyatzis, R.E., Good, D., & Massa, R. (2012). Emotional, social, and cognitive intelligence and personality as predictors of sales leadership performance. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 19(2), 191–201.

DeChurch, L.A., & Mesmer-Magnus, J.R. (2010). The cognitive underpinnings of effective teamwork: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(1), 32–53.

Hughes, A.M., et al. (2016). Saving lives: A meta-analysis of team training in healthcare. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(9), 1266–1304.

Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333.

Battistelli, A., Montani, F., & Odoardi, C. (2019). The role of informal learning in promoting innovative work behavior in a military context. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 92(2), 261–282.

McKinsey 2021 – The future of work after COVID-19, McKinsey Global Institute, Feb 2021.

Li, J., & Wang, X. (2024). The impact of digital transformation on enterprise innovation capability: Evidence from Chinese A‑share listed companies. Scientific Reports, 14, 12345.

Tambe, P., Cappelli, P., & Yakubovich, V. (2019). Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work: Evidence from AI-Enabled Software Development. Management Science.

Noy, S., & Zhang, W. (2023). Experimental Evidence on the Productivity Effects of Generative Artificial Intelligence.

Côté, S., & Miners, C. T. H. (2006). Emotional intelligence, cognitive intelligence, and job performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.51.1.1

Dunst, C. J., Bruder, M. B., Hamby, D. W., Howse, R. B., & Wilkie, H. (2018). Meta-analysis of relationships between leadership practices and organizational, team, and employee outcomes. ECPCTA Leadership Practices Meta-Analysis

Bonini, A., Panari, C., & Mariani, M.G. (2023). The relationship between leadership and organizational adaptive performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 18(7), e0304720

George, G., Merrill, R.K., & Schillebeeckx, S.J.D. (2022). Digital leadership and organizational performance: A contingency perspective. Journal of Business Research, 145, 1–12.

Tarigan, Z. J., Mochtar, J., Basana, S. R., & Siagian, H. (2021). The effect of competency management on organizational performance through supply chain integration and quality, Uncertain Supply Chain Management, 9(2), 283–294

Djalab, Z., Karima, K., Ibrahim, S. B., Naas, S. A., & Al‑hamdany, S. N. (2023). Assessing the impact of competency management on organizational learning: A case of the University of Djelfa, Algeria. Journal of Innovations and Sustainability, 7(1), Article 10.