Skills-Based Pay: What the Research Supports

(and What It Doesn’t)

Skills-based pay is being promoted as the future of rewards: pay people for what they can do, not just the job they hold.

The direction is understandable. Work is changing faster than job architectures can keep up, organisations want more internal mobility, and leaders want pay decisions that support reskilling rather than rigid roles. But the evidence is clear on one point: skills-based pay only works when “skills” are defined, verified, and governed — otherwise it increases inconsistency and perceived unfairness.

This article summarizes what the research actually supports, where skills-based pay tends to fail, and a more defensible model that separates capability, competence and skills.

Why Skills-Based Pay Is gaining momentum

Several forces are driving interest in skills-based pay:

- skills shortages

- rapid role change and task reconfiguration

- increased cross-functional and project-based work

- pressure to improve internal mobility

- concerns about traditional job-based pay rigidity

Research and industry reports consistently highlight positive associations, including:

- improved internal movement

- better alignment between development and reward

- greater perceived fairness when progression is transparent

- using skills as a common language to improve workforce deployment, internal mobility and workforce planning

But these outcomes are conditional, not guaranteed.

WorldatWork’s reporting suggests while more organisations are using skills-based rewards and skills-based promotions — but also indicates many leaders question whether their workforce systems have the design needed to support it at scale.

Three Approaches to Pay — and Why Skills-Based Models Create Confusion

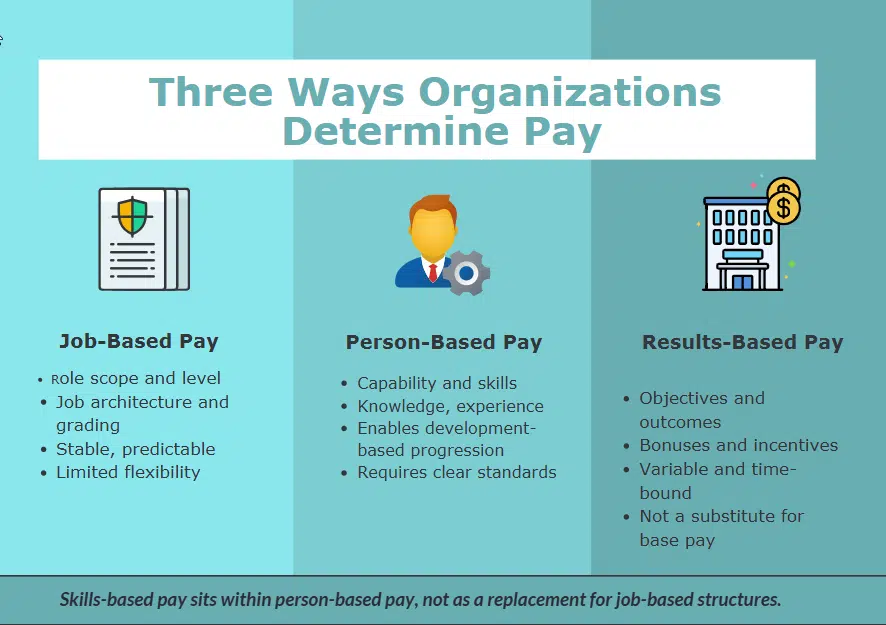

Research on skills-based pay sits within a longer history of how organisations design reward systems. Traditionally, most pay structures draw on one or more of three approaches:

Job-based pay – Pay is anchored to the role — its scope, responsibilities and level. This remains the dominant approach in most organisations.

Person-based pay – Pay reflects what an individual brings to the role — knowledge, skills, abilities, qualifications or experience.

Results-based pay – Pay is linked to outcomes — performance results, objectives, incentives or bonuses.

Skills-based pay is often presented as a replacement for job-based systems, but in practice it is a form of person-based pay — and this is where confusion commonly arises.

Much of the literature uses skills as a catch-all term that includes knowledge, qualifications, experience and abilities. In rewards research, these are often grouped under “knowledge, skills and abilities” (KSA) or similar constructs.

This creates ambiguity when organisations attempt to operationalise skills-based pay. Without clear distinctions, credentials, experience and task-level skills are bundled together — making it difficult to define what is actually being rewarded.

This is where separating capability, competence and skills becomes essential.

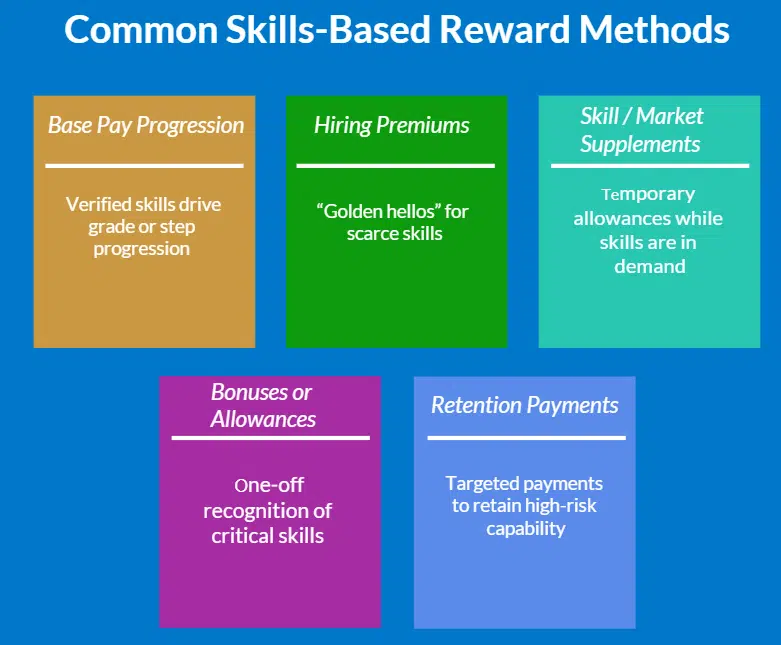

Skills-Based Pay vs Skills-Based Reward: Why the Language Shift Matters

Recent academic literature increasingly refers to skills-based reward rather than skills-based pay.

The distinction is subtle but important.

Skills-based pay typically refers to permanent base salary changes or grade progression.

Skills-based reward is broader and includes one-off payments, such as “golden hellos”, allowances – market or skill supplements paid while a skill remains critical, or supplements- retention payments for high-demand or high-risk capabilities.

This reflects the reality that organisations apply skills-based approaches in multiple ways — not all of which should permanently alter base pay.

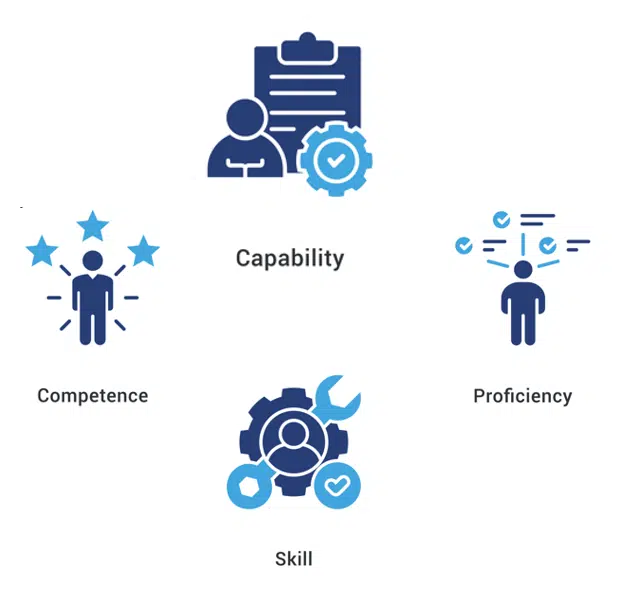

Why Capability, Competence and Skills Must Be Distinguished

In practice:

Capability describes readiness — qualifications, certifications, training and experience that indicate potential to perform.

Competence describes demonstrated performance — consistent, observable application of capability in context.

Skills describe task-level abilities — specific actions that may require detailed verification where risk, quality or safety matter.

Many skills-based pay initiatives fail because they reward capability signals (credentials or experience) or declared skills, rather than demonstrated competence.

Distinguishing these elements allows organisations to reward progression in a way that is fair, transparent and defensible.

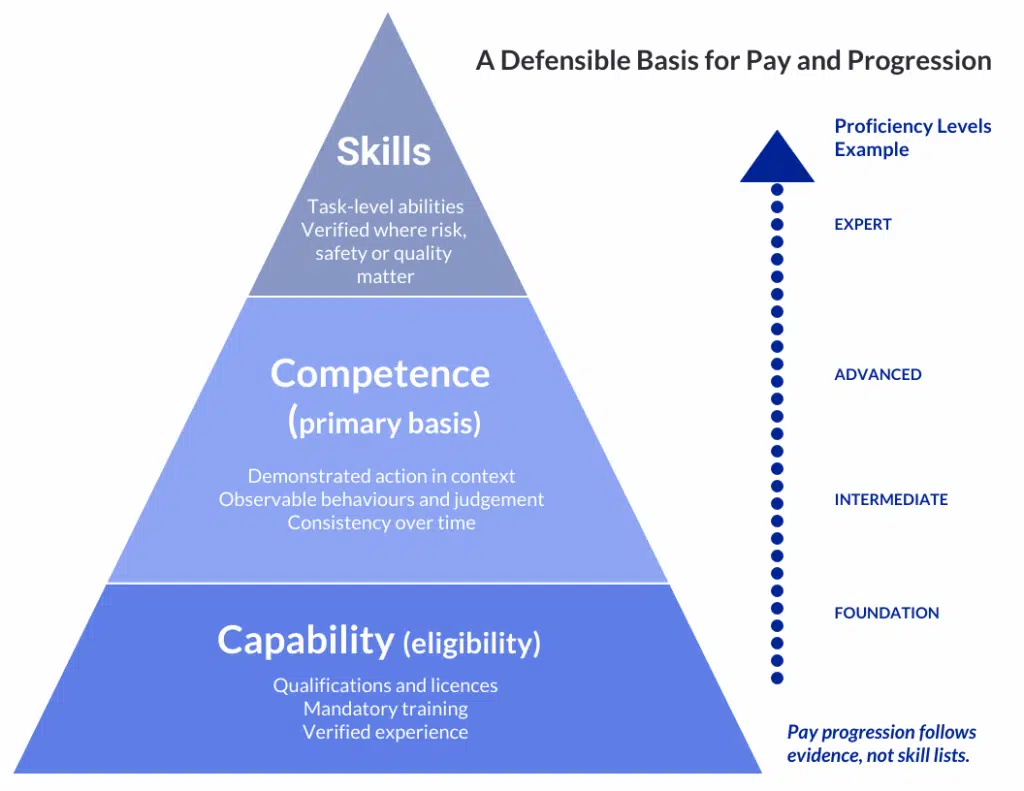

Proficiency Levels Matter More Than Skill Lists

One of the most overlooked elements in skills-based pay design is the absence of clear proficiency definitions.

Pay decisions require more than identifying whether a skill exists — they require clarity on how well it is applied.

Proficiency levels (for example, Foundation → Intermediate → Advanced → Expert):

- support consistent progression decisions

- reduce inflation in skill claims

- enable calibration across teams and locations

- provide a defensible basis for pay movement

Without proficiency levels, skills-based pay becomes binary — creating pressure to reward possession rather than performance.

What Research Says Skills-Based Pay Can Improve

Better alignment between development and reward

When rewards reinforce development (clear skill growth paths and recognized proficiency), organisations can drive broader capability-building — particularly in operational and technical environments. Academic evidence from a plant-level study found that a skill-based pay program was associated with improved plant performance outcomes (productivity, labour cost per part, and quality outcomes). Academy of Management Journals

Internal mobility and agility are often cited benefits — with important caveats

Mercer focuses on the “skills foundation” required for these practices, including taxonomy and market alignment; its Skills Library uses large-scale data collection that targets millions of online profiles and job descriptions, with updates throughout the year to add emerging skills and remove obsolete ones.

Where Skills-Based Pay Goes Wrong

Common Design and Implementation Risks – Most failures are not about intent — they’re about measurement, evidence, and governance.

Design flaws

Skills are too generic (not role-linked)

Many skills-based approaches start by importing a market-facing skills library built from large-scale scanning of job postings and online profiles. These datasets are useful for building an initial taxonomy and tracking demand trends, especially for emerging skills. Organisations adopt broad taxonomies but can’t translate them into defensible pay decisions.

Such taxonomies reflect job postings and self-described resumes/profiles. They should be treated as a starting baseline. They need to be refined to particular role context and supported with proficiency definitions and verification before being used for high-stakes decisions such as pay.

Deloitte highlights that many organisations are still early in effectively classifying and organizing skills, even where efforts are underway.

Structural flaws

In practice, skills-based approaches are usually implemented through existing people systems, including:

- job architecture and job levelling processes that incorporate skills

- career architecture frameworks that define progression through skills and competence

Problems arise when skills are layered onto these systems without clear definitions, proficiency standards or verification methods.

Skills are also often pulled into performance management alongside behaviours and objectives. Many organisations use values and behavioural expectations as key criteria for pay decisions; paying separately for technical skills creates a disconnect that can weaken trust.

The research highlights predictable downsides when skills-based pay is poorly designed:

- specialist career ladders can encourage over-specialisation

- organisations reward breadth by paying for unused skills

- systems become overly complex and hard to sustain

- skills drift from role requirements, reducing credibility

These risks reinforce the need for role-based structures and clear competence definitions as the foundation for any skills-based reward approach.

Evidence flaws

Skills are self-reported or inferred, not verified

If pay is tied to unverified skills claims, overstatement and understatement become a real risk. Independent assessment data from Workera (skills self-assessment vs tested proficiency) shows substantial mismatch between self-perception and assessed results — highlighting why self-reports are a weak basis for high-stakes decisions like pay.

No shared proficiency standards

In the absence of well defined and differentiated proficiency level standards assessment of needs and staff skill levels can vary by manager, site, or team. This inconsistency undermines fairness.

Bias and Inequity Risks

- Systems reward visible or digitally traceable work.

- Interpersonal and contextual skills are over or under valued

- Gender, tenure, and role-type disparities.

Note on use of AI: Inference not verification

Many organisations are now using AI tools to help identify skill requirements and build skill profiles at scale. This includes extracting skills from job descriptions and learning content, scanning internal documents, and inferring skills from work history or project records (for example, using enterprise copilots and similar tools to summarize experience and suggest relevant skills).

Used well, AI can accelerate two activities:

- Skills discovery and taxonomy building – AI can help surface emerging skills, standardize language, and identify likely skill requirements from job content.

- Skills inventory and profiling – AI can assist in creating an initial view of what skills people may have based on role history, training records, project experience, or self-descriptions.

AI can infer that a person is likely to have a skill. It cannot reliably confirm proficiency, judgement, or performance in context without validation.

For skills-based pay, the risk is straightforward: if AI inference replaces evidence, it can amplify the same problems as self-reporting — inconsistency, inflation, and fairness concerns.

Practical rule: use AI to accelerate identification and mapping, then apply proficiency standards and verification where the skill affects pay, safety, quality, or risk.

Why Skills Alone Are a weak basis for pay decisions

A skill is typically a task-level ability. Pay systems, however, need to reward reliable contribution in context, not just capability in theory.

In the I/O psychology literature, skill-based pay is usually defined as a system that provides additional pay only after employees demonstrate the skills/knowledge/competencies being rewarded — i.e., it assumes formal certification or verification, not self-declaration. SIOP

This distinction matters because in real workplaces—especially regulated or high-risk environments—what differentiates competence is not “having a skill” but applying it correctly under real conditions.

A More Defensible Model: Capability + Competence + Skills

A practical evidence-based approach is to treat skills-based pay as part of a broader structure:

Capability: baseline readiness (eligibility)

Capability covers credentials that infer readiness:

- qualifications and licences

- mandatory training

- verified experience

This is a foundation, but not proof of competence.

Competence: remains the core basis for progression and reward

Competence is performance evidence:

- consistent delivery of role responsibilities

- judgement and application under real conditions

- observable competency indicators and standards

This is where pay progression becomes defensible.

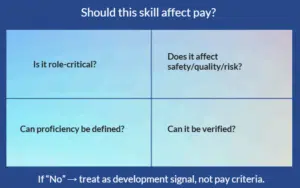

Skills: targeted modifiers (where detailed verification is needed)

Skills should be rewarded when:

- they materially affect risk, safety, quality, or productivity

- the skill can be verified (observation, test, evidence record)

- the organisation can define proficiency levels clearly

This aligns with how skills-based pay is commonly framed in research: additional pay is earned after demonstration/certification of the rewarded capabilities.

SIOP

The Productivity and Misalignment Angle: Why Verification Matters

OECD research on skills mismatch links misallocation of skills to productivity outcomes and indicates that improving skill allocation toward best practice can be associated with measurable productivity gains (the report provides a quantified example for New Zealand).

The practical implication for pay: if you can’t trust the skills data, you can’t trust the basis for pay decisions

Practical Guidance for 2026: Skills-Based Pay Without the Risk

Before you implement (or expand) skills-based pay, you should be able to answer:

- Are skills explicitly linked to role requirements (not generic libraries)?

- Are proficiency levels defined and calibrated across teams/career pathways?

- Is there a verification method (assessment/observation/evidence) for skills tied to pay?

- Are you distinguishing capability (credentials) from competence (performance evidence)?

- Can pay decisions be explained and defended consistently?

If the answer is “not yet,” the path forward isn’t to abandon the idea — it’s to strengthen the underlying framework and evidence model first.

Research-backed – takeaways

Skills-based pay is most defensible when:

- skills are role-linked

- proficiency is clearly defined

- demonstration is verified

- competence (performance in context/on the job) remains the core signal

Related Resources

If you’re reviewing skills-based pay or skills frameworks for 2026, these resources may help:

Capability, Competency & Skills — What’s the Difference?

A practical explanation of how capability, competence and skills fit together, and why the distinction matters for pay, performance and mobility.

Competence Debt: The Hidden Risk Building Inside Organisations

Why frameworks become outdated or unverified over time — and what to fix first.

Competence Debt Diagnostic (10 minutes)

Identify whether your organisation has usable competence data — and where gaps are building across roles, assessment and evidence.

Skills & Capability Inflation

Why skills profiles can look stronger than reality, and how to reduce inflation through proficiency standards and verification.

Internal Mobility Is Broken — And How Capability Data Fixes It

How role clarity and evidence-based competence data improve internal movement, career ladders and succession decisions.

Performance Management: What Effective Systems Really Measure

Why performance should be anchored in role responsibilities and evidence — and where competencies and skills fit (and don’t fit) in appraisal.

Request a walkthrough

If you’d like to pressure-test a skills-based pay approach against your current role and competency structure, we’re happy to review what will be defensible and sustainable in your context.

FAQs

FAQs: Skills-based pay and evidence-based reward design

Short answers to common questions about skills-based pay, verification, proficiency levels and defensibility.

What is skills-based pay?

Skills-based pay is an approach where pay progression or additional pay is linked to verified skills or capabilities an employee demonstrates, rather than being determined only by job title or tenure.

Is skills-based pay the same as skills-based reward?

Not exactly. “Skills-based pay” usually refers to changes to base pay or pay progression. “Skills-based reward” is broader and can include one-off payments, allowances, premiums, or retention bonuses tied to skills.

Does skills-based pay replace job-based pay?

In most organisations it doesn’t replace job-based pay entirely. It is typically layered onto job architecture, job levelling and career structures — and works best when skills requirements are linked to defined roles and levels.

What are the most common skills-based reward methods?

Common methods include base pay progression linked to verified skills, hiring premiums for scarce skills, temporary market/skill supplements, bonuses tied to critical skills, and retention payments where specific skills are difficult to replace.

Why do skills-based pay programs fail?

Common reasons include generic skill taxonomies not tied to roles, reliance on self-reported skills, lack of proficiency definitions, inconsistent manager standards, and insufficient verification or evidence — leading to fairness and defensibility concerns.

Do you need proficiency levels for skills-based pay?

Yes. Skills lists alone don’t support defensible pay decisions. Proficiency level definitions clarify what “foundation”, “advanced” or “expert” actually mean, and enable consistent progression decisions across managers, teams and locations.

Can training completion be used as proof of skill?

Training completion is evidence of exposure, not proof of competence. It may support capability readiness, but ideally pay decisions require stronger evidence of demonstrated performance or verified proficiency.

Should technical skills be part of performance appraisal if we use skills-based pay?

Not usually. Technical skills are typically better treated as performance enablers and reviewed through capability/competency assessment and development planning. Performance appraisal should focus on role responsibilities (what was delivered) and values-based or core behaviours (how it was delivered), supported by evidence.

Can AI be used to identify skills for skills-based pay?

AI can help identify skill requirements and build initial skill profiles by analyzing job content and background information. However, AI-generated skills should be treated as a starting hypothesis — not verified proficiency — and should be validated before being used for pay or progression decisions.

What is the most defensible approach to skills-based pay for regulated or high-risk roles?

A layered approach is usually most defensible: capability (credentials and readiness) establishes eligibility, competence (demonstrated performance in context) provides the core basis for progression and reward, and skills are verified in detail where risk, safety, or quality require it.

References

-

Deloitte Insights. The skills-based organization: A new operating model for work and the workforce (2022). Deloitte

-

Ledford, G. E. Jr. Skill-Based Pay: HR’s Role (SIOP Science / SHRM) (2011). SIOP

-

Lawler, E. E. III, Ledford, G. E. Jr., & Chang, L. Who Uses Skill-Based Pay, and Why They Use It (1992). USC Center for Effective Organizations

-

McGowan, M. A., & Andrews, D. Skills mismatch, productivity and policies (OECD) (2017). OECD

-

Mercer. 2023/2024 Skills Snapshot Survey report (skills-based talent management / reward frameworks) (page summary). Mercer

-

Murray, B., & Gerhart, B. An Empirical Analysis of a Skill-Based Pay Program and Plant Performance Outcomes (Academy of Management Journal) (1998). Academy of Management Journals

-

Workera. Analysis on self-assessed vs tested skill levels (2024). workera.ai

-

WorldatWork (Workspan Daily). The Rise of Skills-Based Rewards, and What You Must Do About It (2025). worldatwork.org