Bias in Workplace assessment

Bias in work place assessments – workplace assessment is high-stakes—and vulnerable to bias. This guide explains where bias creeps in (observation → processing → interpretation), the most common cognitive and emotional biases, and concrete steps to reduce them through better tools, rater practices, and governance.

How assessments are used (and why accuracy matters)

Assessment is a common but high stakes practice in organisations used for;

- Hiring the right people

- Shaping organizational culture via core competency assessment

- Assessing and developing technical competency

- Assessing and developing leadership competencies

- Ensuring Compliance – for example health & safety behaviours

- Improving productivity via Performance Appraisal

- Evaluating Staff engagement levels

- Assessing organisational climate and culture

So, getting it right is critical. Assessment is very prone to bias . When organizations don’t get it right trust, quality and compliance suffer.

Is bias inevitable?

When we think of assessments, we think of giving a rating or score that represents the demonstration of a work task, a responsibility, a behavior or other performance standard.

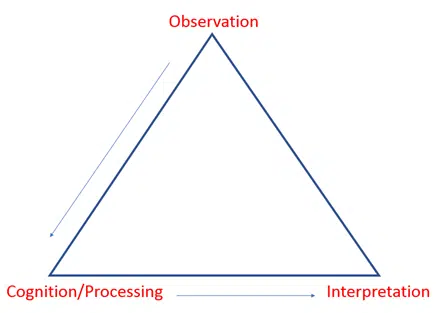

But there is a sequence of events that underlies this judgement that we are not consciously aware of.

- Observation — noticing/recalling behaviours or evidence.

- Processing — comparing what was seen with an explicit or implicit standard.

- Interpretation — integrating signals into a rating/comment.

Bias can enter at each stage, but you can minimise it with design and practice.

The judgement process

1. Observation

Assessors must identify relevant information that they will use as a basis for their judgment. That is they must recognise what is relevant and actually perceive it, then store it in memory.

The observational process is influenced by many conscious, unconscious, situational and personality factors. Research has shown that assessors shown the same video of an assessee will pay attention to different aspects of their activity or behaviour.

2. Cognition/Processing

This is the phase in which assessors retrieve the information they have gathered and use contextual information and their own prior knowledge to make sense of it.

They make use of a categorisation mechanism – a comparison with some sort of standard – implicit or explicit.

An explicit standard would be a very specific indicator or statement in the assessment tool.

However, in most cases, the standard is not specific. In these cases, the assessor will compare what they have observed with an implicit standard. A standard derived from their own beliefs and experience; their own idea of competency/performance and some specific examples they can recall.

Examples used include people assessed in the past, recall of their own level of performance and skills in a similar context, and of staff and colleagues with different levels of experience and expertise.

3. Integration/Interpretation

The information from the observation and processing phases is reviewed. It is weighted and put together into a cohesive mental picture. From here assessors make judgements which have to be translated into a format used by the assessment tools – typically a rating scale and comments.

The strength and clarity of their mental picture will affect the assessor’s confidence in their judgment.

Where it goes wrong

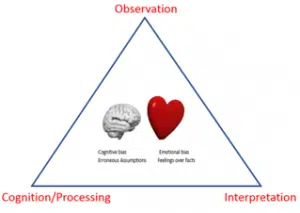

The assessment process is prone to bias at all stages. Bias is a systematic error, or deviation from the truth, in results or inferences.

Biases can operate in either direction: underestimation or overestimation of the true situation. Bias stems from our thoughts and our feelings.

Cognitive bias

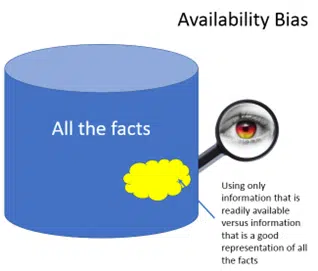

Availability bias – use of information that is easily available rather than looking at the whole range of information that exists.

Recall bias – we remember better recent events, the first and last of a sequence of events (better than middle ones. Negative more than positive experiences, dramatic events over the routine. We tend not to remember things that happened in a different context..

Anchor effects – information on a previous assessment used as a basis for current assessment – not a completely independent evaluation.

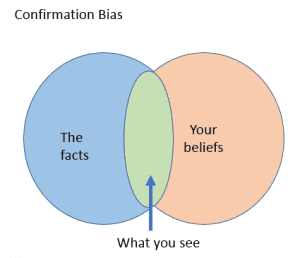

Confirmation bias

Selective perception

- expectations and stereotypes about people and situations affect what is seen and heard.

- tendency to see and hear those things that confirm existing beliefs, and to filter out things that don’t agree.

Emotional Bias

Feelings trump facts. Our feelings influence how we think.

Wanting to be liked – assessments more favorable than true opinion

The halo effect – the overall impression of a person is applied to assessments of specific attributes. Those who are more attractive tend to be rated more positively on any dimension. Many research studies have found performance appraisals are primarily a measure of the staff/supervisor relationship, not the staff member’s actual performance .

Self Assessment Bias

People tend to rate themselves optimistically, overestimate their ability to understand others and overestimate insight into their own motives.

What can be done to reduce bias

What we can do about bias depends on the perspective we take on assessment. There are 3 prevalent perspectives. Use all in combination.

Treat assessors as trainable

- Train awareness of sources of bias

- Run calibration to align on rating scale anchors and what “meets” looks like.

- Require examples tied to indicators for high/low ratings.

- Train to evaluate behaviours, not people; avoid using self-performance as the benchmark.

- Frame marginal results as development opportunities.

Assessors are fallible - assessment format to reduce error

- Use terminology relevant to your organization

- Define specific indicators (one behavior per line) and clearly explained scale anchors.

- Include some reverse scored items to prevent/identify blanket selection of the same rating

- Choose the right scale: Yes/No for strict standards, Frequency for development scans, Agreement for values/citizenship.

- Prefer 7-point scales (people avoid extremes; 5-point leaves only three usable points).

- Have a NULL (not observed – neither agree nor disagree = no assessment).

- Hide prior ratings to reduce anchor effects

- Space out the timing of assessments to reduce contrast effects, (the tendency to make the assessment different than the preceding one(s).

- Use auto-scoring aligned to indicators; discourage free-form overall scores.

- Provide clear instruction on the form.

Divergent opinions may be valid

For values based behaviours and core competencies that are less well defined (e.g., professionalism, integrity), variation can reflect differences in the observation context. Assessments may be complementary perspectives and equally valid. Use 360 feedback surveys as developmental, not pay-linked, input for these perspectives.

Bias-reduction checklist

- Indicators specific, observable; levels (if used) step up by scope, independence, risk, complexity.

- Scale anchors unambiguous explanations

- Prior ratings hidden; journals available to reduce memory bias.

- Require an example for any extreme rating.

- One calibration session per cycle; spot-audits for rater anomalies.

- Separate certifications (credentials) from competency evidence.

- Keep values/citizenship in performance (no proficiency levels); keep role capabilities in the competency framework (with or without levels).

- Document changes (author, date, publication status)

- Keep old versions for data integrity.

Put it to work

- Define competencies and indicators in your competency library and map to competency requirement profiles

- Run assessments with clear instructions –

- Capture evidence (documentation, work samples, observations, simulations, peer feedback and journal entries).

- Review skills gaps analysis and analytics to identify any rater anomalies

- Plan and track development to close gaps

- Re-assess on a time frame to match risk or regulatory requirements

References

Gomez-Garibello, C. , Young, M. (2018) Emotions and assessment: considerations for rater-based judgements of entrustment. Medical Education 52: 254–262

Gingerich A, Kogan J, Yeates P, Govaerts M, Holmboe E. (2014) Seeing the ‘black box’ differently: assessor cognition from three research perspectives. Medical Education 48 (11):1055–68.

Gauthier G, St-Onge C, Tavares W. Rater cognition: review and integration of research findings. (2016) Medical Education 16;50 (5):511–22.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kazdin, A.E. (1977) Artifact, bias, and complexity of assessment. The ABC’s of reliability. Journal of Applied Behaviour Analysis 10. 141-150