Critical Thinking Skills in Talent Management

Critical thinking is the capability to interpret information, analyze it, evaluate its quality, draw sound inferences, and reflect on one’s own thinking. In modern workplaces it underpins safe decisions, problem solving, and resistance to misinformation. This guide explains the competency, introduces respected thinking models, and shows practical ways to build and assess critical-thinking capability across roles.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking combines interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, supported by metacognition (awareness of how we think). It is related to problem solving and creativity but remains distinct: critical thinking tests the quality of information and reasoning before action, while problem solving and creative thinking generate options or novel solutions.

Why it matters now

Information risk: The digital age, and especially the rise of social media, and AI, has brought an explosion of information and unprecedented access to it. But this is an environment rife with misinformation, ‘fake news’, bias, and unverified claims. See our article on mis and disinformation. Teams need the skill to judge credibility, bias, and missing context.

Complexity & stakes: Healthcare, engineering, and technology roles deal with complex problems with many variables, interactions and hidden agendas. Decisions have serious consequences. Critical thinking skills help to evaluate these issues in depth, gather and review evidence, and apply logic rather than emotion in coming to a position, reducing errors and incidents.

Better decisions: Critical thinkers weigh evidence and alternatives, improving quality, speed, and transparency of decisions.

Everyday work: Policies, standards, and data volumes keep growing. People need a repeatable way to see though the noise to insight.

Thinking models used in practice

Blooms taxonomy

Widely used for competency and learning design. It differentiates cognitive tasks (remember → understand → apply → analyze → evaluate → create) and helps write competency indicators and learning outcomes at the right level.

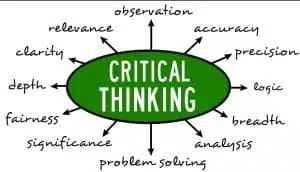

Paul–Elder framework (Foundation for Critical Thinking)

Frames “elements of thought” (purpose, question, information, concepts, assumptions, inferences, point of view, implications) and “intellectual standards” (clarity, accuracy, precision, relevance, depth, breadth, logic, significance, fairness). These are excellent points for competency indicators, reviewer prompts and assessor training.

Disposition: will people use the skill?

Ability isn’t enough; people also need a disposition toward critical thinking.

Weak disposition often shows as:

- Jumps to conclusions or procrastinates; relies on opinions.

- Close-minded; denies own bias; gives up at first difficulty.

- Uses unreasonable/hidden criteria to judge arguments

Weak disposition often shows as:

- Jumps to conclusions or procrastinates; relies on opinions.

- Close-minded; denies own bias; gives up at first difficulty.

- Uses unreasonable/hidden criteria to judge arguments

Strong disposition looks like:

- Inquisitive; seeks to be well-informed.

- Open to alternatives; willing to revise opinions with new evidence.

- Honest about bias; diligent in gathering relevant information.

- Values reasoned inquiry; persists through complexity.

Critical Thinking Assessment

Assess both skills and, where relevant, disposition. Evidence should be observable and tied to indicators.

Abilities typically assessed

- Problem framing and clarity of the question.

- Identifying necessary information; separating fact from opinion.

- Evaluating arguments; recognizing assumptions.

Drawing warranted conclusions; explaining rationale.

Common instruments (examples only)

- California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) assesses problem analysis, interpretation, inference, evaluation of arguments, explanation (providing evidence, assumptions, and rational decision-making), induction, deduction, and numeracy (quantitative reasoning).

- The Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT) assesses induction, deduction, credibility, and the identification of assumption

- The Test of Everyday Reasoning (TER) looks at abilities for analysis, interpretation, inference, evaluation, explanation, numeracy, deduction, and induction.

- Watson–Glaser™ II Critical Thinking Appraisal assesses inference, recognition of assumptions, deduction, interpretation, argument evaluation

- The California Critical Thinking Dispositions Inventory (CCTDI) assesses truth-seeking, open-mindedness, analyticity, systematicity, critical thinking confidence, inquisitiveness, and maturity of judgment

- The California Measure of Mental Motivation (CM3) assesses learning orientation, creative problem solving, mental focus, and cognitive integrity.

Note: choose tools that fit role risk and context; many are licensed and require trained administration. If you define your own critical think competency you can use competency assessment

Can Critical Thinking be learned?

Yes —Cambridge University has a basic guide for exploring these skills at school and in the workplace.

Training transfer improves when skills are taught in context. General exercises help, yet people apply the skill more reliably when practice uses their domain problems and they receive feedback on reasoning quality. Equip teams with:

- Scenarios drawn from real tasks, including conflicting evidence.

- Prompts aligned to the Paul–Elder standards (clarity, relevance, logic…).

- Manager guides that ask for reasoning, not just conclusions.

- Deliberate practice (short, regular case exercises)

One thing is clear – to be able to think critically about something a certain amount of knowledge of it is needed. Experts differ from novices in the extent and depth of domain knowledge they have – enabling them to see the “deep structure of problems” and find solutions to seemingly new situations.

How to develop critical thinking skills across roles (practical steps)

- Define the competency in your competency library with clear indicators and (if used) levels.

- Map to roles ; set higher levels for high-risk decisions.

- Set evidence standards (what counts as proof: case write-ups, observation checklists, simulations, peer review).

- Run assessments ; require examples for high-stakes ratings, and identify skills gaps

- Develop via scenarios, after-action reviews, decision journals, and targeted micro-learning.

- Re-assess on a timetable that matches risk and change.

Use this starter set as a base, then tailor indicators to your risk profile and job families.

Publish to your competency library, map to relevant roles, and assess and identify skills gaps, generate individual development plans.